John Bliss

Police Officer

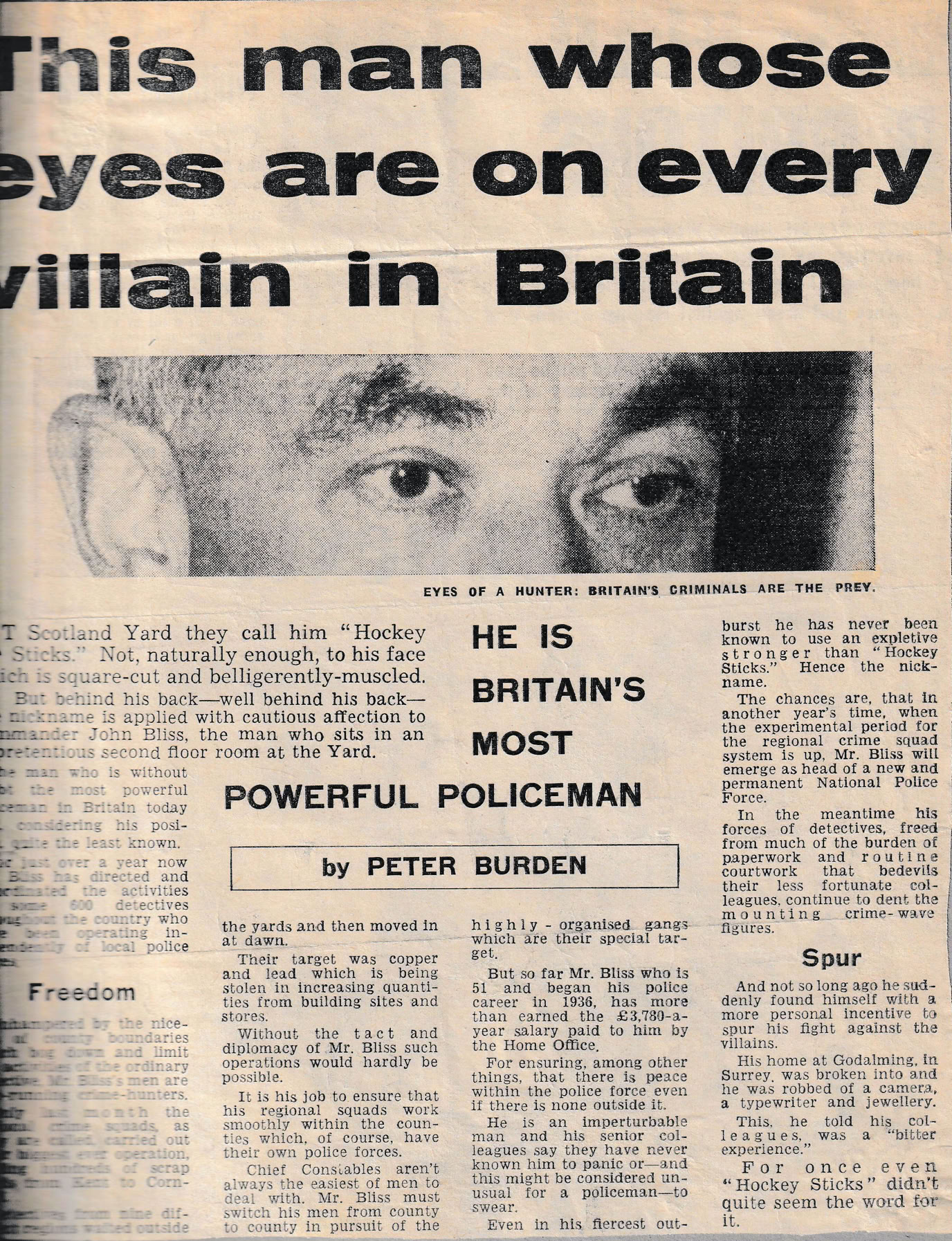

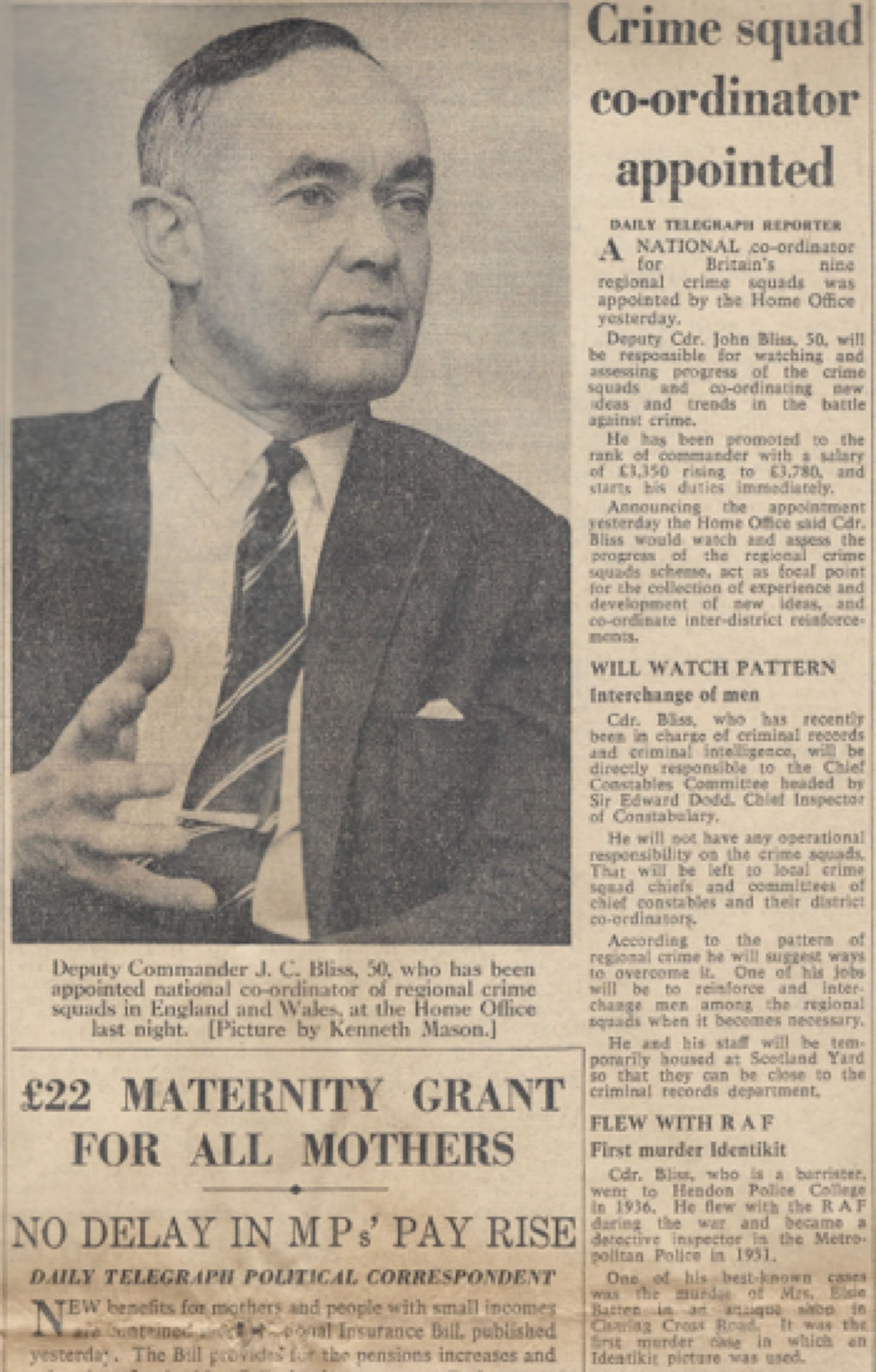

DAC John Cordeux Bliss (Who’s Who / Wiki) QPM, 1914 - 1999, was founder of The Regional Crime Squads, which evolved first into the National Crime Squad and then into the Regional Organised Crime Units of The National Crime Agency. He was also a fighter/bomber pilot during World War II.

JCB was born on the 16th of March 1914 in Finchley, London; son of Herbert Francis Bliss and Ida Muriel Hays, and grandson to William Bliss of Bliss Mill, Mayor of Chipping Norton, and Alfred Hays, musical instrument manufacturer and importer, theatre ticket agent and music publisher. The first Principle of St Hilda’s College in Oxford, Esther Burrows (neé Bliss) was his great aunt (her daughter Christine was the second).

He spent the first four years of his life in Finchley, before moving briefly to Ewelme in Oxfordshire when his father, who was too old to fight, was posted to land army duties during WW1 (Herbert kept a diary throughout this time). JCB was educated at Ovingdean Hall, near Brighton (later Ovingdean House), then Haileybury (his page is here), where he also sent his son Tom, but had to leave without taking his National Certificate because Herbert could no longer afford the fees (Bliss Mill had passed from family management in 1896 and Herbert was now a self-employed tweed designer and salesman).

Pilot Officer John Bliss

(taken in the USA, July 1941)

JCB was an insurance clerk from 1932 until he joined the Metropolitan Police in 1936. He was then fast-tracked, on the Trenchard Scheme, through the newly-formed Metropolitan Police Collage in Hendon, the police's answer to Sandhurst, where he was mentored by Joe (later Sir Joseph) Simpson, who was then teaching at the college. JCB's best friend at Hendon was John Gaskain who by chance had also been at Haileybury, though they'd not been close at school as they were in different houses and years. (John Gaskain stayed in the police throughout the war, and was already Assistant Chief Constable of Norfolk by 1942, something JCB felt keenly when he finally left the RAF in 1946 after his second year in hospital as, still, a Detective Inspector).

Policing was a ‘reserved occupation’, so JCB was not allowed to join up in 1939 as he'd wished. But volunteer fire-watching during the Blitz made him determined to do more than help clean up after the Luftwaffe. So when the rules changed to allow 'experienced' pilots to enlist, he hinted he could fly a plane, when he'd merely crossed the channel as a passenger - once. He was accepted by the RAF in March 41.

The first entry in his RAF log book is for 22nd July 1941, the date he started learning to fly in the USA. He stayed there for two years, volunteering (he said he was volunteered) to train pilots as no one else would. He was at Dothan (Alabama) in October 42, and back in England by February 43.

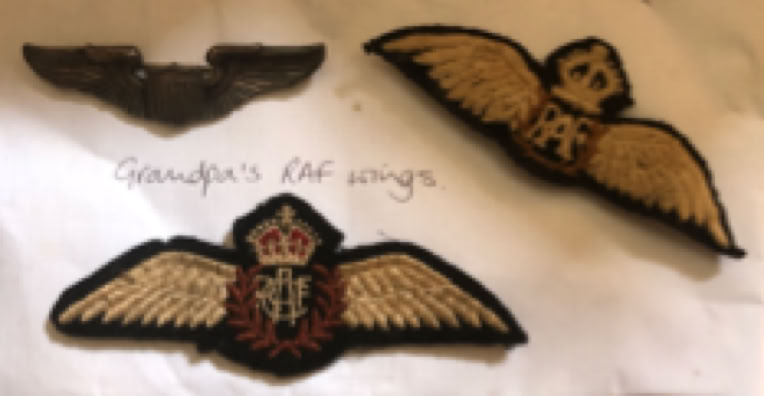

JCB did not talk much about his war, but he left a note for his grandson Jack with his RAF 'wings' and USAF wings badge (right) - which his mother Ida wore on her coat for the rest of her life: "I still have much respect and indeed affection for the American Air Force, who taught us not only to fly but also very good air-discipline, especially how to fly in formation (close to other aircraft), and indeed I suspect that such helped my survival chance!"